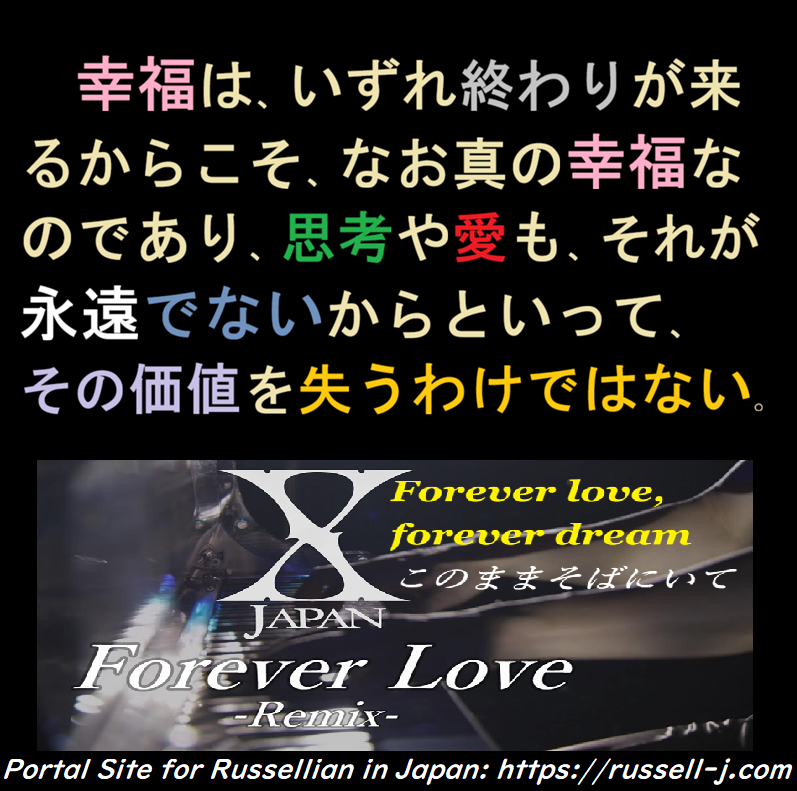

幸福は、いずれ終わりが来るからこそ、なお真の幸福なのであり、思考や愛も、それが永遠でないからといって、その価値を失うわけではない。

Happiness is nonetheless true happiness because it must come to an end, nor do thought and love lose their value because they are not everlasting.

Source: Whati I Believe, 1925

<寸言>

「永遠の」愛を誓う――宗教の信者とそうでない人との違いは?

たとえば、「永遠の愛を誓う」といった表現のように、「永遠の」「永遠に」という言葉は日常の中で比較的気軽に使われています。しかし、このとき人々が思い描いている「永遠」の中身は、実は一様ではありません。宗教を信じている人と、特定の宗教を信じていない人とでは、その意味合いが異なりますし、宗教を信じている人の中でも、一神教の信者と多神教の信者とでは、想定している世界観が大きく違っています。

多くの一神教、とくにキリスト教やイスラム教では、「信じる者は救われる」という考え方が強調されがちです。善良な信者は死後に天国へ行き、信仰を拒み、かつ邪悪な者は地獄に落ちる――そのような構図が語られることが少なくありません。もっとも、キリスト教と一口に言っても教派はさまざまで、たとえばカトリックでは、天国と地獄のほかに「煉獄」という概念があり、死後に浄化の過程を経て天国に至るとされています。もっとも、現実の政治の世界では、あたかもその采配役を自認しているかのような言動を見せる人物(たとえば、トランプ大統領)もいますが――ここではあくまで比喩として触れておきましょう。

多神教においても地獄を想定する宗教は存在しますが、その描かれ方は、一神教に比べると残酷さがやや緩和されているように見える場合が多いように思われます。もっとも、これは外部からの印象にすぎず、実際のところはどうなのでしょうか。

さて、死後の世界を疑いなく信じ、神の存在にも一片の疑問を抱かない熱心な信者の中には、「この世で善い行いをしていれば、来世では救われる」と確信している人が少なくないように思われます。その結果として、この世における苦しみや不幸、いわば「現世の地獄」に対して、どこか距離を置いた態度をとる人が現れることはないでしょうか。キリスト教やイスラム教の原理主義は、その一つの典型と見なされることがあるかもしれません。

だからといって断定するつもりはありませんが、異教徒が大量に亡くなる出来事には比較的無関心である一方、自分と同じ信仰をもつ人が少数でも殺害されると強い怒りを示し、その報復として多くの異教徒や無神論者が殺されることには、あまり心を痛めない――そのように見える場面があるのも事実ではないでしょうか。これは私の被害妄想にすぎないのでしょうか。

一方、日本人の多くは、特定の宗教の信者ではなく、天国や地獄が現実に存在していると本気で信じているわけでもありません。皮肉なことに、そうした人々のほうが、他人の幸福や不幸に対してむしろ敏感であり、相手が異教徒であっても、もし自分に力があれば助けたいと考える傾向が強い、と言えるのではないでしょうか。

日本人が「永遠に」とか「永遠の」といった言葉を使うとき、それは「自分が生きている限りずっと」という意味であったり、「あの世から見守っています」といった慣用的な言い回しであったりします(もちろん、本当にそのようなことが可能だと信じているわけではありません)。それは一種のレトリックであって、永遠の命や来世を信じていないにもかかわらずそうした表現を用いることが、不誠実だということにはなりません。

強い、あるいは排他的な信仰をもつ人たちは、日本人のこうした考え方や感性を、果たしてどのように理解するのでしょうか。

Swearing "Eternal" Love -- What Is the Difference Between Believers and Non-Believers?

For example, expressions such as "to swear eternal love" show how casually words like "eternal" or "forever" are used in everyday language. Yet what people have in mind when they use the word "eternal" is far from uniform. Its meaning differs between those who adhere to a religion and those who do not, and even among believers, the worldview assumed by adherents of monotheistic religions differs greatly from that of believers in polytheistic traditions.

In many monotheistic religions -- particularly Christianity and Islam -- the idea that "those who believe will be saved" tends to be emphasized. Good believers are said to go to heaven after death, while those who reject the faith and are deemed evil are consigned to hell. That said, Christianity itself is far from monolithic. In Catholicism, for example, there is the concept of purgatory, distinct from both heaven and hell, where souls undergo a process of purification before ultimately reaching heaven. Meanwhile, in the real world of politics, there are also figures who behave as if they see themselves as arbiters of such ultimate destinies (for example, President Trump) -- though this is mentioned here only as a metaphor.

Polytheistic religions, too, sometimes posit the existence of hell. However, the way it is portrayed often appears, at least from the outside, to be less severe than in monotheistic traditions. Still, this may be nothing more than an external impression. What is the reality?

Now, among devout believers who have no doubts whatsoever about the existence of God or the afterlife, there are many who are convinced that as long as they live virtuously in this world, they will be rewarded in the next. As a result, might there not be some who maintain a certain distance from the suffering and misfortune of this world -- what might be called "hell on earth"? Religious fundamentalism in Christianity or Islam may be cited as a typical example.

I do not wish to make sweeping claims, but there are occasions when it seems that the mass death of people of other faiths is met with relative indifference, whereas the killing of even a small number of one's own co-religionists provokes intense outrage. In such cases, the large-scale killing of "enemy" unbelievers or atheists in retaliation may not appear to trouble the conscience as much. Is this merely my own paranoid perception?

By contrast, many Japanese people are not adherents of any particular religion and do not seriously believe that heaven or hell actually exists. Ironically, those who do not believe in heaven or hell often seem more sensitive to the happiness and suffering of others, and more inclined to help them if they can -- even when those others belong to a different faith.

When Japanese people use expressions such as "forever" or "eternal," they usually mean something like "for as long as I live," or they employ conventional phrases such as "I will be watching over you from the other world" (without truly believing that such a thing is literally possible). This is a form of rhetoric. Using such expressions despite not believing in eternal life or the afterlife is not, in itself, a sign of insincerity.

How, then, do people with strong -- or even exclusive -- religious beliefs understand this way of thinking and this kind of sensibility that many Japanese people have?

ラッセル関係電子書籍一覧 |

ラッセル関係電子書籍一覧

ラッセル関係電子書籍一覧

#バートランド・ラッセル #Bertrand_Russell