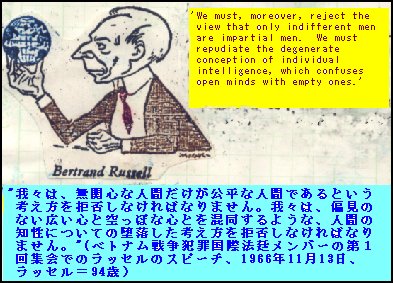

* 右上イラスト:第37回「ラッセルを読む会」案内状から.

希望も恐怖も全て自分自身に集中している人

最高の勇気を身につけるために、もう一つ必要なものがある。それは、今さっき(直前に)私が自己にとらわれない人生観(非個人的な人生観)と呼んだものである。希望も恐怖も全て自分自身に集中している人は、とても沈着冷静に死(というもの)をながめることはできない。なぜなら、死はその人の情緒的な世界を全て消滅させてしまうからである(注:安藤貞雄訳では、「そういう態度は、その人の情緒的な世界をすっかり滅ぼしてしまうからだ。」となっている。しかし、'it' は「そういう態度」ではなく、「死(というもの)」と解釈するのが文法的にも自然だと思われる。)。ここでもまた、私たちは、抑圧(抑制)という安っぽく安易な方法をしきりに勧める伝統と出会う。(即ち)聖者は「自我」を捨てることを学ばなければならない、肉欲を抑えなければ(禁欲生活をしなければ)ならない、また、本能的な喜びをあきらめなければならない。これは実行可能である。しかし、その結果はよくない。禁欲主義の聖者は、自分自身の快楽を放棄(否定)したあとで、他人の快楽も否定する。そして他人の快楽の否定は、自分の快楽の否定よりももっと容易である。心の奥底には(他人に対する)ねたみ'がずっと居座り続けており、そのねたみにそそのかされて、'苦しみ'は人を高貴にするものであり、それゆえ苦しみを与えることは正当である、と考えるようになる。ここから、価値の完全な逆転が生じる。(即ち)善いものは悪いとされ、悪いものは善いとされる。これらの害悪は全て、善い生活を探求するにあたって、否定的な命令に従い、自然な欲望や本能を拡大伸張させなかったことに原因がある。人間性の中には、努力なしで自我を超越させてくれるものがいくつかある。そのなかで最もありふれたものは、愛(情)であり、とりわけ親の(子供に対する)愛である。それは、一部の人においては、(その対象が)人類全体を包含するくらい一般化されている。もう一つは、知識である。ガリレオは、特に慈悲深かったと推測すべき理由はまったくないが、彼はその死によって挫かれない一つの目的のために生きた。もう一つは、芸術である。しかし、事実、人は自分の体の外にあるものに興味を持つならば、いかなる興味であっても、その興味の数だけ、その人の人生は自我(自己)にとらわれないものになる。それゆえ、逆説的に聞こえるかもしれないが、広く生き生きとした興味を持っている人のほうが、自分の心身の不調にしか関心のない惨めなヒコポンデリー(病気不安症)患者よりも、この世を去ることに困難を覚えることが少ない。このようにして、完璧な勇気は、多くの興味を持った人の中に見いだされる。彼は、自分の自我は世界のほんの小さな部分にすぎないと感じているが、それは、自分を軽蔑しているからではなく、自分以外のものを重視するからである。こういうことは、本能が自由で、知性が活発である場合以外は、めったに起ることができない。この本能と知性の2つの結合(融合)から、享楽主義者や禁欲主義者が知らない、広い物の見方が成長する。そして、そのような物の見方からすれば、個人の死などは瑣末な事柄に思われる。そのような勇気は、肯定的、本能的であり、否定的・抑圧的なものではない。私が完璧(申し分がない)と考える性格の主要な成分の一つとみなしているのは、こうした肯定的な意味での勇気のことである。

|

Chap. 2 The Aims of Education (OE02-150)

There is one thing more required for the highest courage, and that is what I called just now an impersonal outlook on life. The man whose hopes and fears are all centred upon himself can hardly view death with equanimity, since it extinguishes his whole emotional universe. Here, again, we are met by a tradition urging the cheap and easy way of repression: the saint must learn to renounce Self, must mortify the flesh and forgo instinctive joys. This can be done, but its consequences are bad. Having renounced pleasure for himself, the ascetic saint renounces it for others also, which is easier. Envy persists underground, and leads him to the view that suffering is ennobling, and may therefore be legitimately inflicted. Hence arises a complete inversion of values: what is good is thought bad, and what is bad is thought good. The source of all the harm is that the good life has been sought in obedience to a negative imperative, not in broadening and developing natural desires and instincts. There are certain things in human nature which take us beyond Self without effort. The commonest of these is love, more particularly parental love, which in some is so generalised as to embrace the whole human race. Another is knowledge. There is no reason to suppose that Galileo was particularly benevolent, yet he lived for an end which was not defeated by his death. Another is art. But in fact every interest in something outside a man's own body makes his life to that degree impersonal. For this reason, paradoxical as it may seem, a man of wide and vivid interests finds less difficulty in leaving life than is experienced by some miserable hypochondriac whose interests are bounded by his own ailments. Thus the perfection of courage is found in the man of many interests, who feels his ego to be but a small part of the world, not through despising himself, but through valuing much that is not himself. This can hardly happen except when instinct is free and intelligence is active. From the union of the two grows a comprehensiveness of outlook unknown both to the voluptuary and to the ascetic; and to such an outlook personal death appears a trivial matter. Such courage is positive and instinctive, not negative and repressive. It is courage in this positive sense that I regard as one of the major ingredients in a perfect character.

There is one thing more required for the highest courage, and that is what I called just now an impersonal outlook on life. The man whose hopes and fears are all centred upon himself can hardly view death with equanimity, since it extinguishes his whole emotional universe. Here, again, we are met by a tradition urging the cheap and easy way of repression: the saint must learn to renounce Self, must mortify the flesh and forgo instinctive joys. This can be done, but its consequences are bad. Having renounced pleasure for himself, the ascetic saint renounces it for others also, which is easier. Envy persists underground, and leads him to the view that suffering is ennobling, and may therefore be legitimately inflicted. Hence arises a complete inversion of values: what is good is thought bad, and what is bad is thought good. The source of all the harm is that the good life has been sought in obedience to a negative imperative, not in broadening and developing natural desires and instincts. There are certain things in human nature which take us beyond Self without effort. The commonest of these is love, more particularly parental love, which in some is so generalised as to embrace the whole human race. Another is knowledge. There is no reason to suppose that Galileo was particularly benevolent, yet he lived for an end which was not defeated by his death. Another is art. But in fact every interest in something outside a man's own body makes his life to that degree impersonal. For this reason, paradoxical as it may seem, a man of wide and vivid interests finds less difficulty in leaving life than is experienced by some miserable hypochondriac whose interests are bounded by his own ailments. Thus the perfection of courage is found in the man of many interests, who feels his ego to be but a small part of the world, not through despising himself, but through valuing much that is not himself. This can hardly happen except when instinct is free and intelligence is active. From the union of the two grows a comprehensiveness of outlook unknown both to the voluptuary and to the ascetic; and to such an outlook personal death appears a trivial matter. Such courage is positive and instinctive, not negative and repressive. It is courage in this positive sense that I regard as one of the major ingredients in a perfect character.

|