Dear Bertrand Russell

[Chapter 4] Philosophy: Foreword

'... I imagine that philosophers will occupy themselves by studying less and less more and more intently. If they do this they will be able to survive the ruthless scrutiny of their governments, if they do not their heads will be removed regardless of the geographical location of the rest '

| |

|

|

While Russell insisted on a clear division between his work as a technical philosopher and his work as a social thinker and man of action, he was quick to point out that his early achievements would not enlighten anyone if his opposition to nuclear war failed.

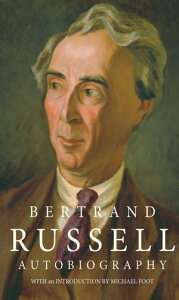

Russell first became well-known as a pioneer of mathematical logic; Iater, as a social philosopher, his influence became wide-spread. He thus likeness his life to that of Faust, as beking divided into two distinct periods. The first period occupies the years up to 1914, during which time Russell set himself the task of discovering whether there was any truth in mathematics. His magnum opus, Principia Mathematica, a joint work with A. N. Whitehead, was first published in 1910. It was of considerable bulk, and in a somewhat down-to-earth manner was conveyed to the publishers in an old horse-drawn carriage. With equal irreverence it was cast on to a rubbish-dump and burned after they had done with it, but not before the co-authors had contributed L(pond)50 each to the cost of its publication. Like Einstein's theory of relativity, the Principia is said to be completely understood by only a few people. Russell, in a letter to two women who assert their appreciation of the work, insisted:'... I cannot believe that both of you have read Principia Mathematica. Hitherto I have only known of six people who have read it, three Poles who were liquidated by Hitler, and three Texans, who were absorbed by osmosis into the general population.' Russell dated his second Faustian period from August 1914, and if the Principia had a select readership, he was now to aim at the many: 'The First World War diverted my thoughts to matters of more immediate practical moment, from which I was led on to considerations of political and social philosophies', he explained in 'My Own Phnosophy', an unpublished 1946 essay.

His first book on social philosophy, The Principles of Social Reconstruction, published in 19 16, deals with the whole range of problems which would have to be faced in creating a new society. Russell did not stand aloof and remote; he made these social questions the province of Everyman. A debunker of pretentious mystification, he could never be accused of boring the pants off anyone. His works like Marriage and Morals and The Conquest of Happiness have a wide appeal, and his classical History of Western Philosophy is a brilliant account of the philosophy of others. A fifteen-year-old wrote appreciatively, ', . though some adults think I am too young to understand your books, I find them stimulating and very clear and concise.' Yet Russell never sacrificed the intellectual rigour of his philosophy at the expense of being popularly understood. 'Commercial popularization is not a good thing', he held, 'because it involves distortion through simplification. This is difilerent from making available to people the intellectual world of philosophy which can be done without sacrificing the integrity of the ideas involved. It is a matter of ability and style.' In 1957 he was rewarded with the Kalinga Prize for popularizing science.

This section indicates on the one hand the extent to which Russell related his philosophy of life to the complex problems of living it, and on the other hand his work as a technical philosopher. Many letters he received express the moral dilemmas of his correspondents. In this sense he was often seen by the lay public as an oracle, or a father confessor. But his answers are disarming- no voice could be less God-like than Russell's- advising where he can admitting ignorance where he cannot.